Shame as a Tool Against Sexual Survivorship: a Wide-Eyed Forever Unlearning

A meditation on shame, guilt, embarrassment, survivorship, self-flagellation, our mothers as young girls once, sluts, and politicized dishonor. CONTENT WARNINGS for: sexual assault, abuse, predation.

Intro:

There’s guilt for being a woman, a guilt for being alive and daring to be scathed. It trails behind your wake like a scent, and the bloodhounds are the men whose shadows graze against yours under the streetlights, like the dogs that they are. Shame is the sloppy precursor to guilt, which leaves misery and isolation in its aftermath. Through time it came to me from the liminal space in between the double life I occupied, locked bathroom door and dimmed phone screen coldness, that shame is a tool of policing and punishment.

I think of shame in the context of gendered and sexual assault survivorship because the naming and shaming of predators in a set community seldom have tangible repercussions. Moreover, the concept of shame itself is nuanced and an ineffective tool of accountability, for there are some people who can never be ashamed, and some people who learned to write “shame” with their name. I speak particularly for ethnic girls raised in shame-based cultures, but I take most of my insight from a South Asian experience. This meditation on shame reflects on the concept as a fetish, a form of policing, surveillance, racialized assimilation, and where shame meets liberation.

Shame and Sexual Survivorship

I first understood what shame entailed in greater sexual assault survivorship discussions. The only part dirtier than what had happened, might happen, will happen, is the loneliness that came from it. In post, most of the examples of sexual violence I would see replaced the status of victimhood to mean the predator, whose name was now “tarnished” by his prey’s invitation.

“She wanted it because she’s misbehaved.”

“She laid in that man's bed, crazy girl, and expected he wouldn’t do the craziest thing to her.”

“What else happens when you aren’t careful and your skirt darts higher than your fingertips?”

In my own experience with sexual assault, shame exacerbated the disgust that aided my silence. I thought about how my ownership of my body lived and died in those cold messy rooms, those classrooms where I looked older than my age and shouldn’t be scared of the eyes of these older men like a teen girl, and my own bed. How, afterward, I did not talk for the next half of the following day, and only when the sun set did I say something that made my friends coo and their jaws drop, because to me it felt like a stumble from my own misstep.

All I wanted was silence. All I wanted was the coldness of my floor. All I wanted was one of them to come back and finish the job, undo my skull into the splinters of an eggshell dropped to the floor, so I could finally be discarded and forgotten and complete. All I wanted was to live without the weight of something that scathed me every time I spin my neck on a dark walk alone to see who accompanies me in the stillness of the night air. There’s a choir of voices that replays its comments when I am left alone with the image of my own body sometimes. In the end, all I dream about is finding where the zipper lands on my skin so I could unzip it down to my tailbone, scour my skin like a bruised suit with a tumbleweed of steel wool, and watch it flap aimlessly on the clothesline. In the end, I still do not know which parts of my body are mine because I forget I am allowed to say no when someone grabs me or assaults me again.

The norm of victim-blaming culture exists as a punishment for women or people of other marginalized genders who imagine, in an institutional universe where genuine choice is tainted by racialized and gendered historical constructs, that, at a personal level, they dare to ask someone else to acknowledge their agency. Sexual violence is not one isolated event - the Big Trauma as a trademarked sole plot point logged into the timeline of a person like that withers from their memory and their wounds through time - but an ongoing pattern of pushing a hand away from your chest for the third week in a row.

The pain and loneliness that comes from disclosing sexual violence experiences, especially when requesting help from your community due to community shame is sometimes the aftershock after the initial hit. Shame regurgitates, rinses, and repeats familiar cycles of trauma by making confronting an abuser or seeking help from loved ones who have categorized an act of brutal violence as “sex” or spoiling their child’s “well-kept purity”. Speaking about the violence becomes almost painful, and an emotionally gaslighting replay of the events as the actual assault itself. If our communities cannot speak about what healthy sex looks like, how can they speak about sexual violence?

From expectations of victims dishonoring families or reassigning victimhood to the perpetrator because of the victim’s personal sexual and expressive history, from how they chose to explore their own dating life outside of set norms, to the minutiae of how they may accessorize themselves, falling out of lines of what is permissible to uphold “femininity” or respectability. In this way, shame can be used as violence and a fetish for policing.

Shame and Our Mothers Who Were Once Too Daughters

To see shame as a tool is to first see shame as a fetish. It is a fetish to expect embarrassment from a bride in an insinuated heterosexual marriage as a confirmation that this new world of men, fingers on her body, and consummation - i.e. the “bashful bride” anxiously permitted through ownership into natural human interactions that are shameful and taboo. Another example is the grown woman expectedly bashful around sex, nearing the expiry date of when still marriable between a father and another family, as if her attitude around sex is further a powerful symbol for the family as demure and quiet as she’s expected to be.

Our foremothers tried to warn us about the pain, alienation, and isolation that follows after sexual assault because they too have been lonely lifelong, even when they still wear the souvenirs of their weddings. When the elder women in our communities utilize shame to corner victims of sexual violence, it’s an extension of the age-old “hurt people hurt people”. It is them misdirecting their fears toward the little girl who once fit in their arms, and they could predict how the men in the community may abuse their curiosity and boldness, forcing them to grow up too early in their servitude.

This factor doesn’t negate the harm done by women too. In multi-generational immigrant communities with a particular South Asian understanding of the issue, the context of disclosing sexuality is furthermore a patriarchal and misogynistic problem. From what I’ve gathered from women in my community, it is their way of keeping their daughters safe both from their learned fears, and social constraints of what femininity is as a shield against further potential alienation. This is where shame can be used as a fetish, a tease of embarrassment or omnipresent guilt, or as a tool of policing.

Shame As Policing: Some Jargon, Some Lingo, but Mostly Some Explanations and Roots

There are several cues about what standards of expected generalized, hegemonic femininity look like from formal published research and the lived experiences I’ve passed with many other girls who look and were raised like me over two decades. To homogenize a gendered experience dulls the vivid nuances across many communities forged by colonial capitalist history, even to narrow down this experience to the South Asian region, but can be read as maintaining a binary gender meekness that is just as dangerous.

To be honorable is to be feminine is to be a child in the body of a woman – then a woman in the body of a child. It is to be an accessory to caste-based violence in a South Asian context, as standards of purity and modesty exist as gateways of Brahminical patriarchy against Bahujan people, or the oppressed global majority. Examples of this involve shame through historical breast taxes in South India meant to humiliate Dalit women through shame, appropriation of cultural crafts outside of their erotic sensual celebration or widespread context and gatekept into a dominant caste-only Sanskritized art form, or shame used as a tool against Bahujan victims of sexual violence. It's your features eventually growing into themselves rounder and with more room for kissing, but that being horrible. Even when wanting nothing to do with whiteness, it dictates you as another omnipotent entity paired with the eyes of men in the corner of an empty room. That is the boundary that shame scoots gender-marginalized people into.

By being considered bargaining chips to represent honor, social markers, and boxed-in femininity, the daughter and her sexuality have the power and pressure of representing honor and respect in a family’s community. To be dishonorable is to feel, rawly, and engage with historical explorations of sexuality altered in the psyche, robbed, or culturally shifted due to colonization or Brahminism (the latter from the context of a South Asian oppressor caste person requiring reparations with unlearning). Some of these explorations, which varied per wildly diverse South Asian ethnic communities and status, involve gender non-conforming and third-gender identities, same- and multi-gender relationships not needing to be labeled and separated, and open indigenous erotic sexual pleasuring practices. It is a part of unlearning the depths of psychological colonization, as theorized as a phenomenon by Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, initially in the context of necessary violent African decolonization. We daughters are psychologically plagued with shame and are left to either face or recreate the trauma we inherited, the hard-won habits that crushed the women inside the mothers who raised us in order to callous the shell tested always by someone’s fingers, someone’s eyes, someone’s rancid breath, or someone’s denied administrative application. It is a nurture as natural as the socio-political forces around us.

Unforgettably, to be “dishonorable” in a South Asian context of casteism which transcends religious and national bounds looks like working to undo the covert codes that keep a global Bahujan people the most policed by shame for existing and most disproportionately susceptible to sexual violence. In this way, sometimes the ability to always be behaved and attempt to be honorable is a privilege afforded only to the caste privileged, the white aspirational assimilationists, and accessories of assault victim blaming.

All brown girls live under two surveillance states: (1) the sly racialized sphere of the imperialist panopticon and its intel and (2) the shame of their extended families. The only time we are free is when we in some way kill something in ourselves to break free, but that too is followed by mourning.

I think often, as daughters, about how we are gatekeepers for our family’s secrets and facade for its learned survival instincts, even coming from wounded people striking more wounds. Studying gender is not just studying how binary racialized femininity is constructed, but also how masculinity as a performance, and even casteist politicized nationalism, is equally important. In the same way that some brown men out there attempt their salvation in a white woman's pussy, begging for the girl who finds him innately creepy and stinky-dicked to not label him with the animal and uncouth brown women of his kin. Some aunties and uncles attempt their assimilation, too, in the same way by shaming you into accepting predation as your default outside of silence and demurity. I think about how radical it is to understand that this femininity is part of liberal assimilationism and aspirational in power and free from the political and socioeconomic repercussions of whiteness. It is radical to say this trauma that happened to you happened to you. It is your own trauma.

Shame and My Mother Who Was Once A Daughter Too

Sometimes I look at my amma just to witness the gem of a woman before me. If I were to place my palm against my forehead, four fingers down to my brow, I’d have copied her whole face. I often think about how we are reflections of our mothers as who we are in our fears, impulses, and intuitions. It is up to the next generation to sculpt something with it and whether or not to bury their desires. Sometimes when I am again afraid, like when I walk home in the dark and hear a second set of footsteps trail me and must break the facade of feigned strength, I think of her, invoke her, and even pray to her. She cannot say she did not raise me to be like this, and I cannot deny that either because saying that would be denying history.

In retrospect, when I think about the times I have strayed from the boundaries, as detailed above, pre-set for me – the time she found me switching my outfits to crop tops when I went to school, the time she found out I was queer by going through my phone in high school, the time she found an opened condom moving me out of college stuff, the times she’s stalked my Instagram and seen me posed towards the camera in less than half a yard of fabric, or the time she found my short-lived Sex Ed blog detailing antics – I think about how there is nothing different I can nor want to do. In understanding how chaotic, how libidinous and unabashed I am as a person, I have to understand her personhood and where we see each other. Do we still love each other for this history we do not deny, or/and for who we both actually are as people when we are down to our intuitions and fears?

I think of the loneliness my mother and a lot of the aunties around me described growing up, retelling stories little by little of how they were once young women with fathers unhinged and performing a version of policing masculinity, and men who would try to grope them too. In those moments, I thought perhaps there isn’t enough I know about my mother, not in the way that, if we peeled back the masks we donned due to shame in front of each other, we would recognize the person we had spent two decades with.

Sometimes I think about how my mom will crack a raunchy joke after a bit from a TV show or cook meals for my girlfriend who she knows is not my “best friend” because she knows exactly what dishes my girlfriend likes. She can’t know about my predatory adult “partners” from when I was in high school or now, in healing, what I’m up to until four every Friday night. And for now, that is okay. Until we are old, this unlearning, self-actualization, healing thing will be a constant wide-eyed coming of age.

Shame and Perception: A Vibe Shift and Perhaps A Final Case Study

When I first thought about accepting perception, a neutrality neither between rejecting it nor controlling it, to tackle the neverending shame, guilt, and embarrassment for daring to exist, I was watching the Korean action movie Oldboy (2013). I was on thin ice with my grandparents, who had done a deep dive on me, in shock, questioning if what I am is a front for rebellion or perhaps reality (we both knew the answer). In anxiety, I was curled up on my bed watching a movie about a man who loses his memory and is punished for witnessing an act of incest by force into the same crime. The premise seemed all shock value and the use of a form of abuse to test the most taboo of all taboos for box office curiosities, but in the midst of the story I was proven wrong by its sentiment.

The punishment was shame, the concept of living with and in eternal guilt knowing that the protagonist would be embarrassed and re-embarrassed for a taboo out of his control, doomed to forever be a festering secret within him or the agony of being laughed at again for being a despicable member of society. While obviously only talking about the message and not the actual subject matter, Oldboy illustrated the ridiculousness and the qualm of humiliation used as a vehicle for eternal torture.

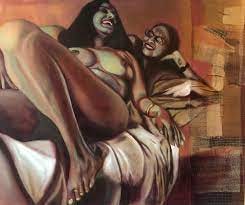

It took me a while to understand what guilt I held in my body, including the velvety richness of my girlfriend’s skin laying on mine. Perhaps it was recognizing that eternal guilt for my queerness, sexual fluidity, reclamation, and my slew of memories of assault and survivorship looked like understanding where and what my ego was: I am. I am seen, and I cannot change that. All I can do is heal, be unabashedly hedonistic and heathen, and care for myself and loved ones while understanding perception towards myself was inevitable and perhaps none of my business.

To unlearn shame is only one part theory; perhaps it is also, knowing some analytical roots, a dialectic process of the self. It was like exposure therapy thrusting myself loud and forward with buckets of anxiety poured into my lungs and abdominal cavity, understanding there is something beautiful about being big, too much, and embarrassing because at the end of the day, it was all me. If someone was to see me as facetious or unappealing, did it magically mean anything more than my own perception and adoration? That a blue coat was now red because someone pointed and called it red? I continue to thrust forward still prioritizing my healing and the safety of the community and those around me, knowing it is a process on my own timeline with things I am not ready to share yet with the ones I love, sometimes because that too needs a period for breathing.

Dealing with shame culture means choosing to be scared because of what the fear of the alternative’s constraints mean. It means seeing my mother's face while laughing in the mirror. It means my girlfriend’s bare, sweaty palm caressing mine as we smile peacefully at the naked ceiling. It means focusing on important things, like Sex Ed and sexual health information. It means reading books about girls who look like me with the footnotes as I kick my feet. It means letting myself cry until I am hiccuping the little girl safely back in me. It means taking one layer off before I leave the house and doing a twirl before I enter a room.

xoxo: vriddhivinay.wordpress.com | linktr.ee/vriddhi | @vriddhiarchives